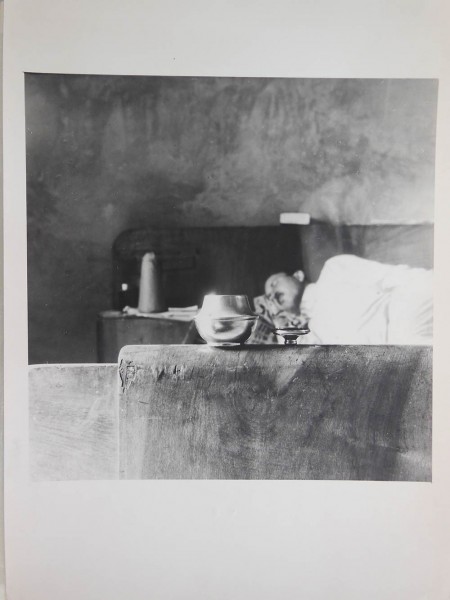

The Gallery Zlotowski has a very particular relationship with Edwart Vignot’s work. At the Salon du Dessin in Paris Edwart greatly admired a purist still life by Amédee Ozenfant that the gallery was showing. Shortly afterwards, he found and photographed his own version of the same still life at the table corner of a Parisian restaurant. This was to be the start of our collaboration.

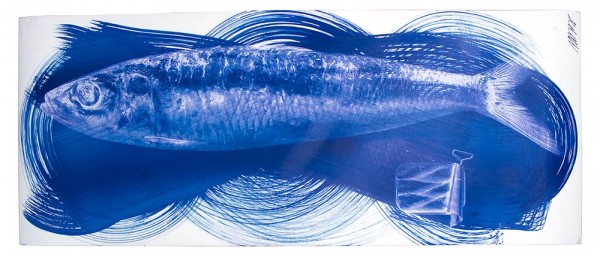

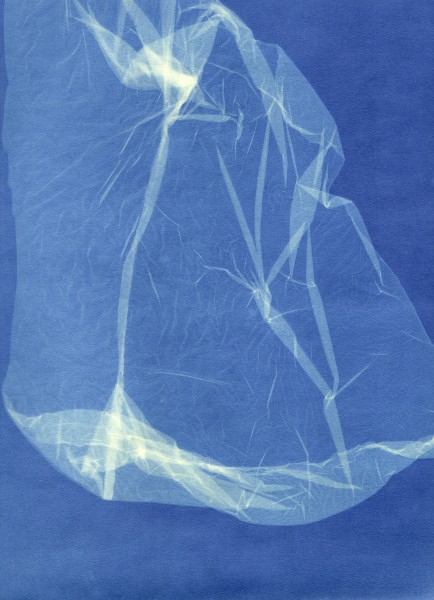

Edwart Vignot’s photos are nourrished with references to the history of art, which becomes his raw material. Scattered waste is reminiscent of Kurt Schwitters’s compositions, wrinkled papers turn into Jacques-Louis David’s drapery. Edwart Vignot joyfully jumps from deep knowledge of art to snapshots and sees the grand masters’ compositions on the traces of the sidewalk. Thanks to an impressive iconography and an exceptional sensitivity to his environment, the photographer detects poetry in the most trivial features of everyday life. He reveals a universe accessible to everyone but that is transformed through his vision. He takes random photos when out walking or on visits to museums. A piece of cardboard stuck to the floor becomes an element of the “broken ear” from Tintin’s famous album. A garbage bag transforms itself into a cat having a wash; papers caught in a cobweb become an abstract composition…

Playful and smart, Edwart Vignot’s work re-enchants reality by enabling artworks to exist outside their materiality. He also helps to understand the obviousness and simplicity of masterpieces. But because art is also a way of embracing the world that surrounds us, his work can be considered as an education of the eye. Each of us can look at a street, a wall or at the walls of an art gallery in Edwart Vignot’s way. And each one of us may have the good fortune to see how beautiful things suddenly become.

Fang Yen Wen

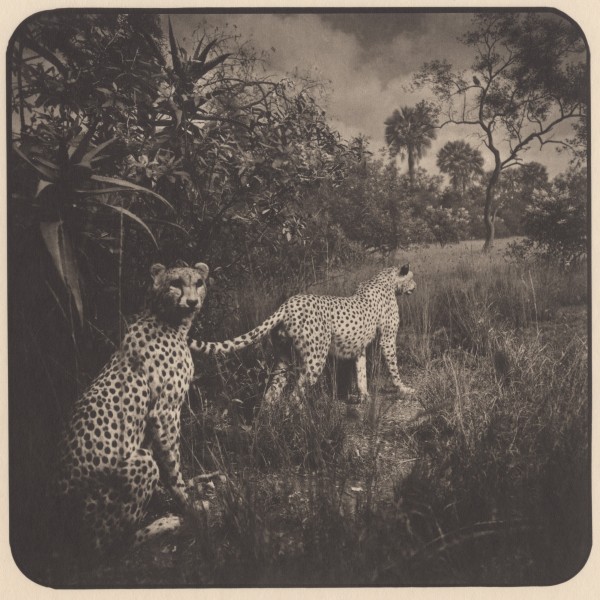

Shinra – The Wide World

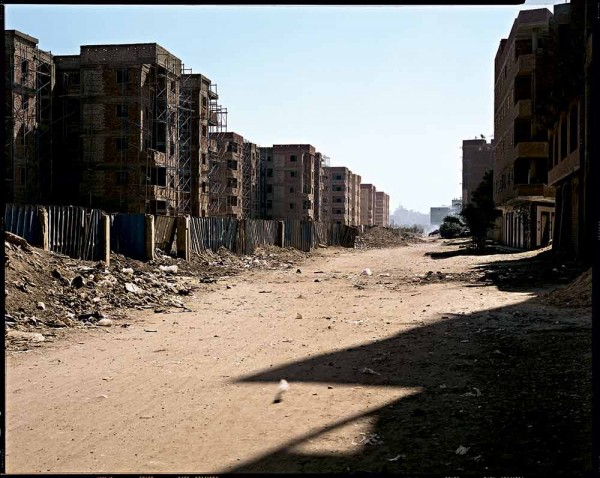

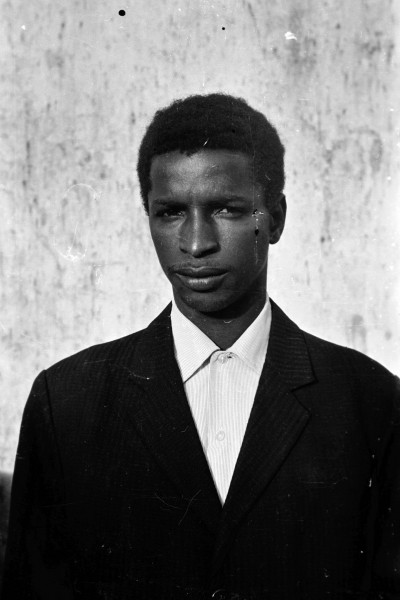

Fang Yen-Wen, a young photographer born in 1994, is an accurate and sensitive observer of Taiwan and its transformations. From his already rich and diverse work, Galerie Zlotowski has chosen to show photographs both elegantly composed and full of poetry. The care for composition and color contributes to a melancholic atmosphere in which disillusioned characters are the silent witnesses of oppression, be it economical, urban, or political.

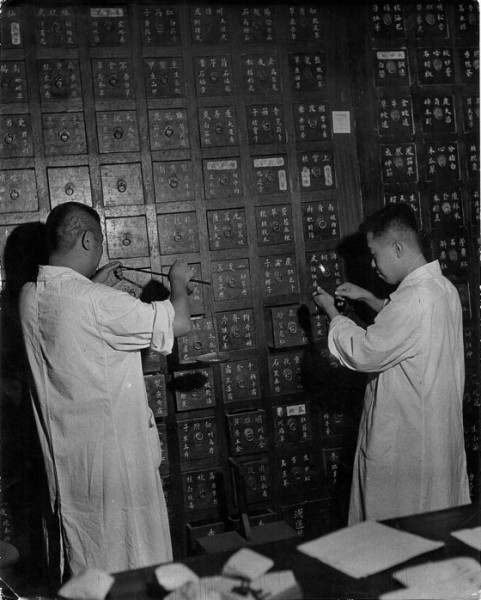

The series dedicated to elderly shopkeepers of Taipei highlights, in heavily detailed compositions, resigned and dreamy figures who seem to have been swallowed by their own shop, waiting for the (definitive?) closing.

Other pictures taken in Japan unveil a harrowing side of Asian metropolises, elegant but dehumanizing. Silhouettes are frozen by the eye of the photographer. Humans become simple pawns in a city turned into a giant chessboard. The strict geometry of the downtown architecture embodies a frame for their loneliness.

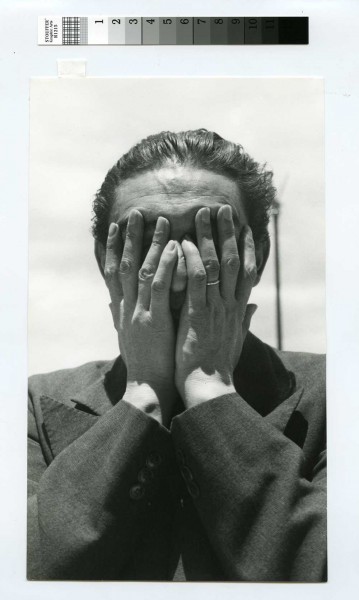

More political, photographs of the Taiwanese sunflower revolution (March 2014) shows demonstrators in a striking way, united and isolated at the same time.

Whatever his subject matter, his characters are more or less at the center of a chaotic scene with a highly-elaborated composition. Bathed in light, thanks to the photographer’s viewpoint, they recover presence and dignity. This constant care about light, often artificial, and to the process of building an image, helps to temper the anxiety contained in the photos which revolve around the ideas of fragility and loss. Maybe as an echo of the threats that weigh upon the territory of Taiwan.