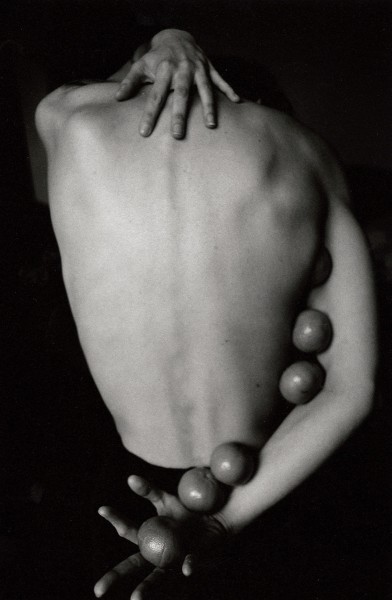

Painting or photography? Ever since chimigram’s creation on the 10th November 1956, as much ink as varnish has flowed in the dbate about the nature of a chimigram. Sometimes classed as a fine arts practice, at other times it’s held to be photography, as if everything was always a matter of category. Often, mention is made of the chemistry at work in the process, whereas it would be more accurate to talk of physics, because it’s primarily about the gradual lifting of a varnish layer covering photosensitive paper. A novel process, the technique combines the physics of paint (varnish, wax, oil) and the chemistry of photography (photosensitive emulsion, developer, fixative) using neither photographic apparatus nor enlarger, and in broad daylight.

In the beginning was one man, Pierre Cordier (Brussels, 1933). While doing military service near Cologne in Germany, Cordier obtained photographic paper to make a dedication to a young German woman. He had bought nail varnish to help identify the bowls in his photo lab: R for developer, F for fixative, L for photographic wash. Instinctively curious, Cordier wrote on his photographic paper with the varnish. With a view to obtaining a black backdrop, he soaked the paper in the developer, aiming to fix the text. However, the varnish did not remain stable. It developed a craquelure and lifted. The chimigram was born and then and there fulfilled the three necessary conditions of Cordier’s future chimigrams: photography, painting and writing.

Many creations and exhibitions followed. The auto-chimigram (Michel Butor); the photo-chimmigram, a 1963 invention (Homage to Muybridge); Jorge Luis Borges (Livrillisible; The Babel Librarye, Ilégibiligram, Dédalogram). In 1976, Otto Steinert {Subjektive Fotografie) said of Pierre Cordier’s work,” A painter would find it difficult to equal the precision of the structures and colours.”

Nearly fifty years later, Gundi Falk (Salzburg, 1966) met Pierre Cordier in Brussels at a reunion at the Museum of Modern Art. Cordier approached her, they engaged in conversation and agreed to collaborate. Thus were born four-handed works, spread over several years beginning in 2011. This opened new horizons for both, revealing yet again the rich possibilities of this decidedly singular medium. A series was produced, going by the names ‘Musigram, Voltagramm’, ‘Even-Odd’ and ‘Friedrich Nietzsche’.

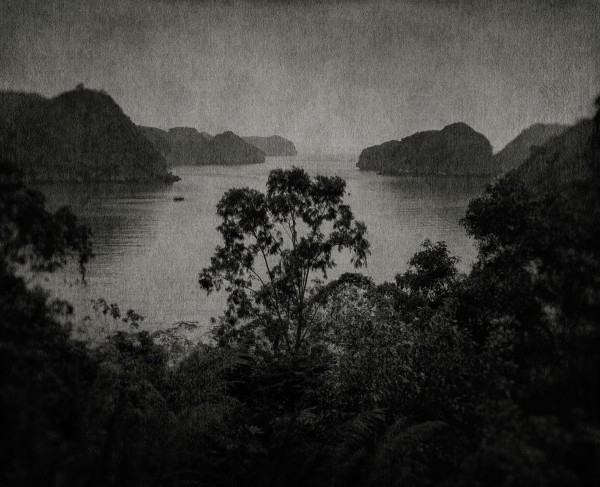

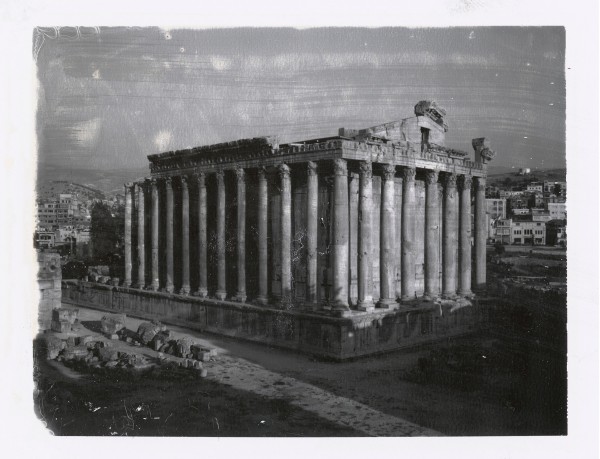

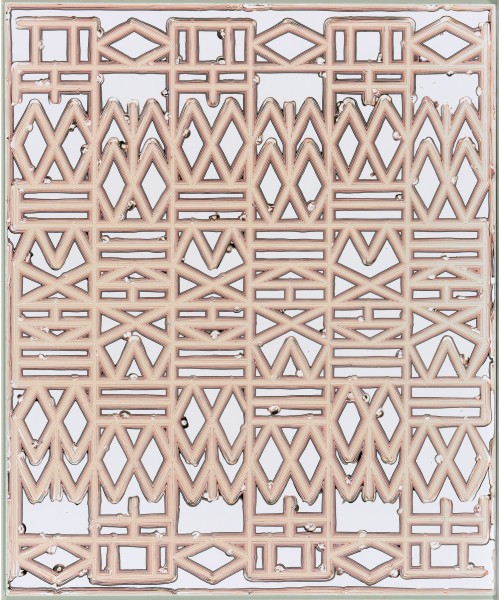

A dancer and actor of Austrian origin, Gundl Falk drew on the fine arts to fuel her drawing, painting, and sculptural practice. For Flak, the chimigram technique was closer to painting than to photography: a fixed image which, from afar, lends itself to confusion -photography? painting – but close up, reveals its organic matter and singular beauty. A process which might appear at first sight unpredictable, but whose chance elements could be tamed, mastered, given time and experience. For several years now, working as a solo artist Gundl Falk has created several series bearing the titles ’Intangible Landscapes’ and Matter’s Whispers’. In fact, it’s less the technique that matters than what one makes of it, using set constraints to further explore the process. The recent series, ‘Becher Variations’, where Falk takes inspiration freely from the photographic series by the German couple Bernd and Hilda Becher, reconciles the ‘Sujektive Fotografie’ of Otto Steinert, angled on experimentation, with the practice defended by the Bechers, jointly revisiting both these movements by means of the chimigram. There is no question of Falk making copies in accordance with the famous photos taken by the Bechers. Rather, it’s in homage and dialogue, where the drawing pre-exists the physics at work in the process. The importance that Gundl Falk gives to the line and stroke joins with the magic of the process, always delivering a unique result which measures the distance between the chimigram and photography.

Whether made by two or four hands, the works presented by Pierre Cordier and Gundi Falk are not multiple prints but unique pieces. Determined to decompartmentalize genres, both of them work to erase this obsession with categories: the chemigram is logically placed on the side of ‘Cameraless Photography’, in the same way as other experiments carried out by Floris Neusüss, Adam Fuss, Thomas Ruff or Susan Derges. An indeterminacy that has resulted in not giving its rightful place to this technique, so singular, unique in the history of art, still largely unknown and too little studied.

Aliénor Debrocq, Auteure and Historienne d’Art

Galerie Gimpel & Müller

The Gimpel & Müller Gallery essentially shows and supports post-war abstract painting. Three trends are privileged : geometric abstraction, lyric abstraction and kinetism.